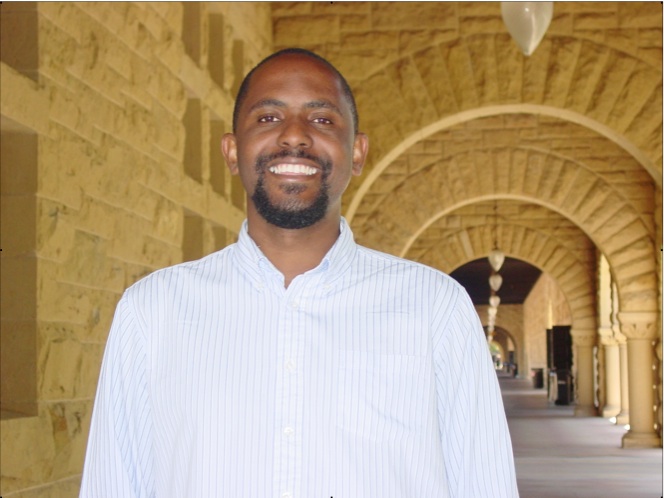

Dr. Tendayi Viki was born and raised in Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe. He is now senior lecturer in social psychology at the University of Kent in England. Currently a visiting fellow at Stanford University, his research interests include intergroup relations and multi-cultural co-innovation. He's also founder of social news site thegoodin.us, which aggregates stories about those who do good in the world. I recently sat down with Dr. Viki to explore the social structure of Zimbabwean villages and their commons-based agricultural practices.

How was it growing up in Zimbabwe?

The cultural influences from the West, combined with a strongly collective culture, made for an interesting mix of ideas and ideologies. Almost every parent aspired for their children to get a great western education. And yet almost every parent also aspired for their children to remain committed to traditional Shona culture. Later in life, I realized that cultures’ sharing the best from each other is probably one of the best ways to tackle some of our global issues.

How is sharing a part of that traditional culture?

In one sense African communities have always known and valued the idea that sharing is important. The community often plays a huge role in every person's success, even here in the US. In Zimbabwe, this is explicitly recognized. There are also boundaries placed around incessant wealth creation, which can be used to harm others. So for example, traditionally in Zimbabwe, rural communities engaged in communal farming. The land is owned by the community, if you want to call that ownership (it’s more like stewardship). Each family is allocated a plot on the basis of some socially agreed rules. Whatever they grow on there is theirs, but they never own the land outright. So it’s a balance between individual ownership and community relationships.

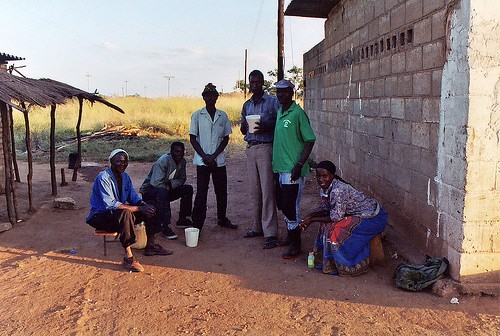

Farmers in Zimbabwe share an after-work beer. Photos of village life by Martin Addison.

Farmers in Zimbabwe share an after-work beer. Photos of village life by Martin Addison.

What is the social structure of the typical Zimbabwean village?

Particular areas have a Chief. The Chief is technically royalty, and he oversees the day to day social affairs of the community. Under the Chief, there are a number administrators called Sabhukus. If, say, my son recently got married and he now needs land for his family, we will go to the Sabuku who will then allocate to us, on the basis of our need. We can use the land, we can build homes on it, we can farm, but we don’t own the land outright. We can’t take it to the bank and use it as collateral for a loan.

So the Sabhuku owns that land?

No, he just holds it in trust for the Chief. The Chief hold the land in trust from the people. They both have some power over allocating it, but neither of them can go to the bank to get money and use the land as collateral or sell the land.

It sounds as though there is a lot of potential in that system for abuse and cronyism. Is that the case? How are humanity’s worst impulses kept in check by the system?

Cronyism is certainly a problem in situations such as these. It is something that probably feeds into the political system on a national level. However, in rural communities there is some recourse through the chief. So if the Sabhuku’s decisions are deemed unfair, a person can appeal to the Chief. For the chief, community cohesiveness is ultimately his goal and duty, so his decisions are strongly influenced by this. It is also important to put in place very strong normative pressures against cronyism. But it can definitely be a huge problem in these communal spaces.

Is that it, or is there more sharing that happens within the community?

There is a lot of sharing within communal communities. It is almost like everything you own can be borrowed by others for use. People help each other with planting and harvesting crops. You just provide some beer and food and invite the whole village to come help and almost everyone comes. People help each other out during weddings, funerals and during many other ceremonies. People also often lend each other tools, and share food whenever necessary. It is considered rude to let people leave your house without offering them food. Not like a cup of tea or coffee. I am talking about a real meal, like lunch or dinner. Whenever I go home and I go to visit relatives, if I make the mistake of visiting more that 2 or 3 of them on any given day, I am usually very, very full at the end of the day after eating 4 or 5 full-course meals! It is considered rude to refuse food!

Greeting a visitor for a meal.

Greeting a visitor for a meal.

When so much is shared in common, there’s a lot of potential for conflict. How is conflict managed?

I think in communal Zimbabwe you will find a lot of what the Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom regards as key factors to the success of the commons.

- The first thing is that the rules governing the use of collective goods are well matched to local needs and conditions. These are also clearly understood by all members of the common and are passed down from generation to generation via oral communication.

- The rights of community members to manage the common is recognized and endorsed by external authorities all the way up to government.

- A graduated system of sanctions is used and community members have access to low-cost conflict resolution mechanisms. Conflicts are resolved by the Chief who can make rulings on issues involving land disputes, theft, and other minor infractions. If the issue is not resolved or the crimes are serious (e.g. rape and murder), this is the kicked to the police to take over.

There is a lot of poverty in Africa. How does that hurt the commons?

There is an historical context to African poverty that is often ignored. But it is also true that social relationships can have a constraining effect on individual autonomy. People some times refer to this as “crabs in bucket.” People in the communal context may constrain individual entrepreneurship just to maintain the social order. This is certainly the experience of some people from collectivist societies. But this is not inevitable. I don’t believe that individual ownership is an exclusive prerequisite for creating wealth. There must be a balance, something like communal capitalism, community capitalism, or, as my friend Neeraj Sonalkar calls it, “relational entrepreneurship.”

Interesting idea! But how would that work?

So these are rough ideas I have. But imagine a community that encourages entrepreneurship but consistently and methodically places constraints, such that the businesses that have the most value are those that facilitate and improve the social relationships among people. Not the kind of social responsibility as in McDonalds paying for a couple of kids to go to University. Sure, that is valuable, but imagine that the actual business, the money-making machine is the one that facilitate better lives for the community. This course requires communal relationships that value and applaud entrepreneurship but frown very strongly at businesses that take advantage of people.

People have embraced the notion that you need individuals to own property for economic development to occur. But this overlooks that clear fact while wealth has been increasing in the West, social relationships have suffered. As such, you have very, very rich people who are also very, very sad people.

Much of the focus of philanthropy in the West is on giving aid to developing nations. I, however, think the West has as much or even more to gain from developing nations. How can Africa help the West?

You need to check out this project, "Design for the First World." I love the idea. I think developing nations have a lot to contribute to the cultural aspects of values and human happiness. Sure the West can provide financial resources, but even this has to be done collaboratively. It has to be a two way street, with the recognition of equal value from both sides. I think that mutual beneficial cross-cultural contact is a totally shareable idea!

You’re currently a fellow at Stanford University. When you look at the school and the city of Palo Alto that surrounds the campus, what do you think that American communities like that one can learn from Africa?

I have really enjoyed my time here. I love Palo Alto’s entrepreneurial culture. There is a real celebration of people starting their own businesses. Also, the community is quite strong in terms of meet-ups, conferences, and workshops. The open source idea is really in the line of communal societies. I think such spaces can really benefit a lot from the study of best and worst practices in the African commons. How do you regulate and allocate shared resources? How do you resolve conflict? These are all important questions in open source communities.