Melinda Blau has been covering relationships and social trends since the seventies. In this special column for Shareable, she draws on her own social experiments as well as stories she collected from others about how to develop meaningful relationships with near-strangers.

Recently, I asked an American woman whether she’d moved to Paris in 1952 because she’d fallen in love with a Frenchman. Without missing a beat, she said, “It’s a little more complicated than that.

The same could be said of the conclusion in Malcolm Gladwell’s “Small Change,” a piece in which he questions the value of social media-based activism:

…[It is] simply a form of organizing which favors the weak-tie connections that give us access to information over the strong-tie connections that help us persevere in the face of danger.

It’s a little more complicated than that. Life isn’t lived in the “either/or” extremes. Today’s social campaigns are not waged on the Internet or off. It’s all of a piece–a “both/and” phenomenon. Modern activists are no different from TV producers, merchants, educators, scientists, sufferers or patients. Social media is but one of the ways they connect.

Likewise, potential activists aren’t willing or unwilling to “persevere in the face of danger.” Most people who participate in high-risk activism go through a developmental process–they read a pamphlet here, go to a speech there, and meet new people. They listen to, and talk about, ideas they’ve never imagined. Some immediately hear the call–and many go on to become leaders. But most foot soldiers of the movement change slowly; radicalization doesn’t happen overnight.

Finally, social ties are not dichotomously weak or strong; they fall along a continuum. The majority of relationships are in the muddy middle, just beyond strangers, just short of friends. Indeed, all of us start out as strangers and then, as bits of information and history are exchanged, we find ourselves in weak-tie territory–the realm of consequential strangers.

Weak ties can morph into stronger ones, of course, especially when people come together to fight a common enemy or to advance a common cause. But it doesn’t matter how far a particular relationship travels toward the strong-tie end of the continuum. All social ties have meaning, and some–even the weakest–can motivate us to put our lives on the line.

For example, Chude Allen, a mid-westerner who came from “good Christian, Republican parents” was at a Carton College in the early sixties when, she recalls, “A redheaded man came up to me and said, ‘Do you want a world in which only the rich people survive, or a world in which everyone can live?’ Right then and there, I changed. He never came back, and yet I’ve never forgotten him.”

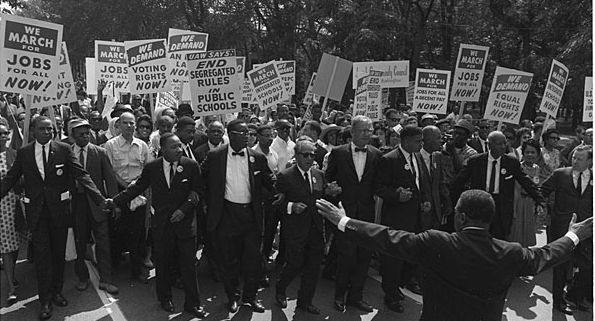

Allen would later apply to be part of “Freedom Summer,” a pivotal three-month campaign that raised the consciousness of the country–and, many believe, marked the beginning of “the Sixties.” Gladwell uses Freedom Summer as a nostalgic example of “high-risk activism” to which, he contends, “weak ties seldom lead.” I wrote about Freedom Summer as an example of the power of weak ties.

This was what I heard from Freedom Summer volunteers: They were thrust into a foreign world, surrounded by people whom they barely knew. Often, those weak ties became stronger because they faced danger together; they didn't start out strong. Jim Kates, another volunteer, recalled his social ties this way:

The only other person I remember being friendly with was the sister of another volunteer — I was never quite sure what she was doing in Oxford, I think maybe she lived there — Mary Volk. David Gelfand was a volunteer, but we were never close friends. One other Wesleyan student in the group, my classmate John Suter trained that week. I liked and respected John, but didn’t know him very well except as someone who liked Gershwin and Wagner. In general, I continued to feel pretty much alone.

Granted, the seeds of activism typically take root in small, tight-knit groups. But it’s more complicated than that. As Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam, author of Freedom Summer, told me when I interviewed him in 2007, “if that’s all that happens, the movement stays local. It doesn’t spread via friends. That’s where consequential strangers are really important. It doesn’t turn on intimates–a movement only gains momentum when it begins to reach beyond intimates.”

In other words, it is “both/and.” Strong and weak ties serve different and sometimes overlapping functions–in social movements as in all arenas of life. Wondering how and whether Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Flickr, or Foursquare might have advanced the cause of civil rights in 1964 is beside the point. This is 2010. We use, and adapt, social media tools–to converse, to post videos, to wrangle our weak-tie networks– because we can. If the technology had been there fifty years ago, Freedom Summer participants probably would have used them, too. The fact is, social media in and of itself doesn’t cause anything. But it adds to our ability to deal with illness, conduct our daily business, or wage war against society’s ills. It’s hard to call these benefits “small change”:

Spreading the word. The Internet enables weak tie conversation–gossip, really–with marvelous efficiency. Gossip has a negative conversation but it’s also our way of maintaining social ties–and deepening them. It causes information to flow. We talk about what’s best, what to be afraid of, what to think about, what’s needed. In a social movement, information is power. The first taste of an idea isn’t necessarily a precursor to action. But there’s no chance of action unless an idea begins to take hold. As Jean Houston, founder of the “social artistry” movement, recently told me, "I can put out a nugget of thought on Facebook and Twitter, and a few hours later, a thousand people are talking about it and creating a community around that idea."

Chronicling the experience. It’s not what someone else had for dinner that keeps us coming back to social media sites, or the news that Mary’s baby slept through the night. It’s the exposure to potential new ideas and experiences that broaden our vision of possibilities. A soldier’s email from a combat zone, a parent’s photos of her child’s participation in the Special Olympic, tweets from Moldavia or Tehran make the unfamiliar real. I’ve been there. I’ve done that. In and of themselves, self-reports aren’t necessarily a call to arms, nor do they count as participation. But one of the most powerful things we do as humans is to bear witness to another person’s struggles–even by reading and commenting on his/her blog. Social media makes us feel less isolated, allows us to speak our piece and share our ordeals. It also inspires at least some of the witnesses to join the fray themselves.

Connecting the participants. In the mid-2000s, thanks to the Internet, Freedom Summer volunteers began to reconnect. Better late than never. They had spent three life-altering three months in the deep South, and when they returned to their home towns in late August of 1964, they were like soldiers returning from battle, shocked and sometimes lonely, because their families, friends, work colleagues had no idea of what they’d been through. “We had no place to talk about it,” said veteran Jim Kates. “We weren’t talking to each other.” They could stay in touch by mail–a first-class stamp then cost a nickel–or place the occasional “long-distance” call. But only a handful did. In contrast, now conversation can flow between them; reunions are easier to organize. They can email one another or log on to Civil Rights Movement Veterans, described as “a website is of, by, and for Veterans of the Southern Freedom Movement during the years 1951-1968. It is where we tell it like it was, the way we lived it.”

Keeping the story alive. Connecting, in person and on line, is also a way to make sure others don’t misunderstand – or forget. “One of the big catalysts for bringing people together,” recalls Freedom Summer veteran Jim Kates, “was Mississippi Burning in 1988. It made us ask ourselves, ‘Who is going to control our story?’ That movie had a catalytic effect on bringing people together. It’s a little like when Holocaust miniseries appeared and reawakened memories.” But Kates and others also went beyond the struggles of the Sixties, participating in other "freedom" movements. Some Freedom Summer volunteers became life-long activists. The Internet enables them connect with others on the same path.

Inspiring new models of participation. Above Nate St. Pierre’s desk is a white board on which the 32-year old has written, “What can you do with a million people today?” The question makes sense when you learn that St. Pierre is the founder of "It Starts With Us,” a site built on the belief that everyone wants to do good, but many of us feel we don’t have the time, the energy, or a life situation that lends itself to high-risk activism. “All it takes is fifteen minutes a week,” reads the welcoming page, “to touch hearts and change lives.” True, calling to cheer someone up, or doing an anonymous good deed isn’t the same as standing on a picket line. But there are many ways to be of value to society–and to share the burden. As St. Clair puts it, “If you can focus the small actions of a ton of people who are otherwise loosely connected, you can have a big impact over time.”

Teaser image via Wikimedia.