“We will rise or fall together, so we better get together!” With these words, Gus Speth, former Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme, opened the Strategies for a New Economy conference this month — an event organised by the New Economics Institute (formerly the E. F. Schumacher Society). Four hundred people convened at the idyllic setting of Bard College, 100 miles north of New York City, to discuss 10 different themes, from responsive government to sharing the commons. Much focus was placed on the potential for worker-owned companies and co-operatives to democratise and re-localise business. Participants were reminded that 130 million U.S. citizens are members of co-operatives and 10 million U.S. citizens are involved in worker-owned companies.

Public banking was a similarly hot topic. Keynote speaker Gar Alperovitz asked poignantly: If the U.S. government keeps bailing out the banks, why not make them public? In this light, people regularly mentioned the Bank of North Dakota, the only state-owned bank in the U.S. in addition to the Puerto Rico Government Development Bank. Comparisons were made with situations in Europe where decentralised decision-making around lending is more common via municipal and cantonal banks.

Another topic that emerged prominently throughout the conference was the value of strong community relationships. The average U.S. citizen, we were told, has half as many close friends as was the case 50 years ago. In this light, the meeting was quite obviously a watershed for many who had felt intellectually isolated with respect to the issues being explored. Re-embedding commerce in real social relationships and seeing exchange as part of social construction that builds a community’s capacity for collective action was presented as a critical aspect of a ‘new economy’ paradigm.

News of inspiring collective action emerged throughout the three days: Germany had produced half of its daily energy from renewables one day in May; eating locally is becoming cliché in U.S. states like Vermont; and, encouraged by news that only 2 percent of U.S. citizens support ongoing subsidies to fossil fuel companies, 350.org is now focusing all its attention on the issue (and, just this week, has generated an unbelievable amount of Twitter activity). I stuck with positivity in my own presentation, sharing 20 of the most exciting examples I’ve found from around the world that I believe are catalysing futures beyond economic growth.

Excitement ran high throughout the event. At both the opening and closing sessions, the crowd responded hungrily to the movement-building rhetoric that ‘our time has come.’ Yet, I felt conflicted. As is often the case at these sorts of events, I loved meeting so many amazing people, yet felt intellectually underdone. I heard, felt, and experienced very little that seemed really new, radical, or profound. With the convening statement asking “What would an economy built on principles of fairness and sustainability look like?” I was left wondering. Sure, there was no shortage of suggestions along the lines of Yes! magazine’s 10 steps we can take now to build the new economy, but what of the macroeconomics? Here, the discussion seemed to get bogged down in old-school, binary thinking — cooperative versus individualistic action; change from ‘the inside’ versus change from ‘the outside.’ Sadly, this seems an all-too-familiar accompaniment to most conferences of this ilk, perhaps due to the heavy influence of academic ‘Boomers’ for whom the ideological legacy of the Cold War remains strong.

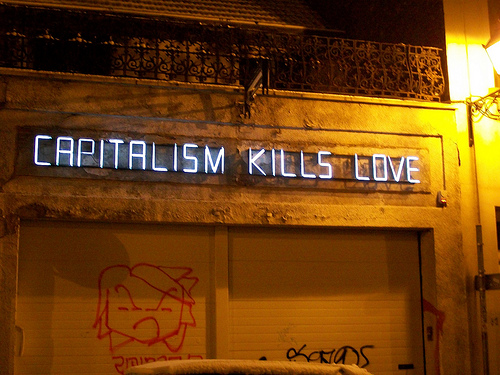

A sign on a closed business points a blaming finger. Photo credit: Future Atlas. Used under Creative Commons license.

When discussions about replacing or reforming capitalism did emerge (e.g. John Fullerton’s ideas around regenerative capitalism), they didn’t seem to get very far. Understandably so, the term capitalism can be so widely interpreted and few people seemed interested in exploring their differences in order to come to an agreement about the common tenets of capitalism they most wanted to address. Hence, when I asked, “What if sustainable futures can’t include provisions for private profits, given such a practice seems to most commonly result in financial inequity, status envy, and subsequent increases in consumption? Do any of us really need more than a fair wage?” the response from panelists and audience members was silence. There seemed an additional tendency towards ethnocentric and mainstream thinking. I felt alone and somewhat out of place in raising topics like Islamic banking, the potlatch as a non-destructive way to approach ego, or matters of sexuality and gender dynamics.

I believe richer experiences can result if such conferences evolve in two ways. Firstly, what if we adopted more meaningful ways to collectively engage? It was great to see the conference organisers embracing Twitter (see the Storify archive here) and involve thousands of people from outside the event via the live stream of many sessions (even more were filmed, with a growing record here). I also really enjoyed the occasions that allowed us to explore our ‘offers’ and ‘needs’ with other participants. Yet, the main methods of participant engagement were standard — sitting through didactic plenaries and parallel sessions, all indoors within a packed agenda. Surely we’re ready to embrace open-space techniques and a little unconferencing? People apparently loved the sociocracy-based session convened by Brian Kelly, from the Gund Institute. Perhaps even more importantly, as participant Venessa Miemis asks in a blog piece, what about events in which we embody action, not just plan for it, like global service jams? A manifestival, as one respondent to Venessa’s blog suggested.

The second avenue I’d suggest for evolving richer conferences relates to participant demographics. At this conference, volunteers did an amazing job in getting so many people together in the one place for three days, and I’m told the organising committee’s support for low-income participants, via scholarships, was substantial. Wouldn’t it be sensational if we could expand diversity at these events in terms of age, ability, profession, and culture? Talk of public banking, for example, recast my mind to the wonderful opportunity I had to hear from 12-year-old Victoria Grant at the Degrowth in the Americas conference in May. As a practical response, I’m thinking of taking along a younger person to my next conference, whether they’ve been invited or not!

Combine exciting methods of engagement with greater participant diversity, and edgy, more valuable conference content should always emerge. In the world of new economics, such content would seem desperately needed. Paradoxically, however, new ideas may flourish even more when we move beyond the subtly disempowering rhetoric of starting a movement or creating a new economy. For me, movements are built around centralising principles that actively legitimise a range of existing, often personal agendas. After all, as the New Economics Institute shows via their recently launched Global Transition to a New Economy map, a diversity of alternative economic futures are already here, they’re just not evenly distributed.

###

For more coverage of the Strategies for a New Economy conference, see this post from the Center for a New American Dream.