Published originally in The Urbanist.

Mott Smith’s background doesn’t immediately suggest “developer.” “My undergrad degree is in linguistics, which taught me that people follow rules of behavior that are completely unconscious, but which you can discover if you watch and learn,” he explains. “Then I played bass in a rock band full-time for two years, which taught me the importance of laying good foundations.” After hanging up his guitar (at least some of the time), he worked for the government and private sector.

Now, as Principal of Civic Enterprise, he’s able to pursue his passion for great neighborhoods. “My partner and I do all kinds of projects that allow us to help make neighborhoods more vibrant, walkable, affordable, and exciting,” says Smith, “both as planners and as principals in developments. We like to forge new regulatory pathways wherever possible. And if we can help make those pathways more available for others to use — such as with the small lot subdivision ordinance in Los Angeles — we feel like we’ve made a contribution, and we are happy.”

Union Station in Los Angeles applies gorgeous architecture to basic infrastructure. Photo credit: Pedro Szekely. Used under Creative Commons license.

Smith recently took a visiting contingent from SPUR on a tour of Los Angeles, his favorite city. We talked to him about what we in the Bay Area could learn from this place that he describes as “so rich in culture and so enticingly misunderstood.”

I’d rather answer the question “what can we learn from each other?” The first time I met (and fell in love with) SPUR, it was through an exchange you did with the Westside Urban Forum in L.A. I was blown away at how similar our perspectives, aspirations, challenges, and complaints are. I now believe the historical period when a place is built determines its form and character even more than its location does. The new towns in the Bay Area have similar issues as the new towns in Southern California, as do the older communities in both places. What I have learned from SPUR and the Bay Area is that it isn’t just L.A., but all of California that continues clumsily to apply a 20th-century, new growth paradigm to existing urban places, with poor results. We need to move beyond planning that cares mostly about zoning and takes no ownership of the city foundations that really matter: infrastructure and the public realm.

You talk about the value of authentic character — which is often difficult in brand-new developments. Can you speak to the importance/advantages of adaptive reuse, of not starting from scratch?

American architecture, planning, and development culture is obsessed with authorship, often at the expense of authenticity. There’s an unspoken sense that urban interventions are only worthwhile if someone can say, “I planned that.” This, however, is narcissistic, limiting, and profoundly anti-urban. It results in the problems the great sociologist Richard Sennett described in his book The Uses of Disorder, namely that urban planners become too preoccupied with stopping unplanned things from happening and, in the end, have no idea how to create. This suburban ethos has invaded our cities over the last 100 years, leaving its DNA in urban renewal, NIMBYism, and the highly scripted specific planning we engage in to the exclusion of real game changers like investment in infrastructure and the public realm, the places hungriest for real planning. At Civic Enterprise we believe that the best neighborhoods have invented themselves over time (generally on a foundation of public infrastructure). And, instead of trying to erase that history, as so many plans and projects implicitly try to do, we want to find that value in organic places and build on it.

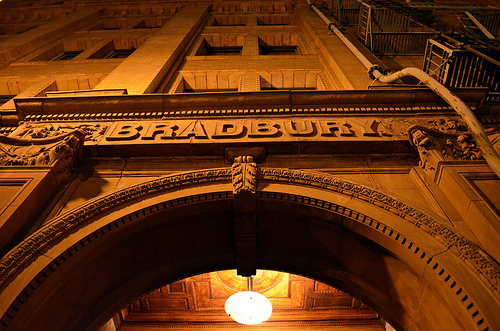

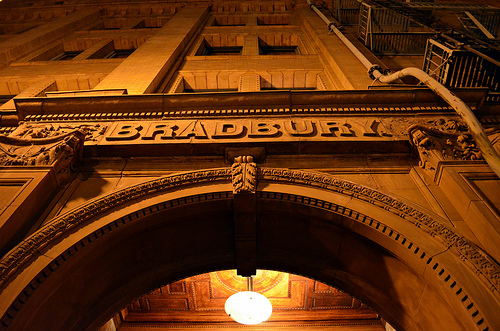

The Bradbury Building was built in downtown Los Angeles in the 1890s. Photo credit: Alex Bandful. Used under Creative Commons license.

So, as someone who is thinking about the cities a lot, what is your favorite…

Urban view: Jamestown, St. Helena, South Atlantic Ocean. A cosmopolitan town of fewer than 1,000 people, built almost 400 years ago, and still largely unchanged. It is the purest evidence I have seen that “urban” is not about how big a place is, but about how it functions physically and how its people decide to relate to each other.

Favorite building: Wow, so many to choose from. The Bradbury Building in Downtown L.A. is one of my favorites. I love it not just because it is an urban geode, but also because of its story. It was designed in the 1890s by George Wyman, a draftsman who was inspired to take the commission after consulting a Ouija board. It sits at Second and Broadway in Downtown L.A., right in the middle of the historic core. It’s like a quiet guest at a loud party who turns out to be the most interesting person in the room.

Favorite city: Los Angeles — so much rich culture and so enticingly misunderstood. I also love Butte, Montana, which, in the early 1900s, thought it was going to be a copper-fueled Chicago and invested in great Richardsonian, bearing-wall skyscrapers that still stand today. Its population now is less than 40,000, but it still retains its immigrant history — Irish, German, Italian, Slavic, etc. There’s even a 100-year-old synagogue downtown that, last I checked, still holds services at least occasionally.

Most impressive urban infrastructure: The canals of Venice, Italy.

Best book/film/work of art about cities: Wings of Desire, a film by Wim Wenders. It’s about über-cool, omniscient angels in Berlin. One falls in love with a trapeze artist and chooses to give up his status and vantage in order to experience real life in the flesh. He becomes a regular, schlubby guy in a bad sweater. But he gets to feel the cold city air, warm himself with fresh coffee, and touch the person he loves. We in the land-use world would do well to do all those things every so often.

##

More from the Urbanist:

- Federal Government Comes Through on Transportation Funding (Barely).In July, Congress passed MAP-21, a rare piece of bipartisan legislation to fund surface transportation for two years.

- The Corporate Campus Embraces Urbanization. Google has proposed a new vision for retrofitting its Mountain View campus as a dense and walkable urban place.

- Member Profile: A Commitment to Authentic Urbanism. Molly Turner, director of public policy for Airbnb, is a self-described “urban planner moonlighting in the tech world.”