Despite reports that suggest the economy and employment are on an upswing, the situation remains dire for many American cities and the people who live in them. Cities across the South and the Midwest whose economies relied on now-dormant factories are beset by bankrupt or corrupt government institutions, while many residents live in extreme poverty. In the nation's metropolitan centers for culture and commerce, a tech-savvy generation of precarious workers face uncertain employment prospects and mounting debt. Meanwhile, American citizens' faith in municipal, state and federal government is dispiritingly low.

It's a recipe for a systemic failure of civic institutions — or an opportunity to rebuild cities as more representative and peer-to-peer entities.

It's an imposing task. With cities still weathering the effects of the recession, making the pitch for innovation and transparency to budget-conscious city officials can be difficult. Compounding the issue is that citizens embittered toward civic institutions may not see or understand the benefit of such initiatives.

Image by opensourceway on Flickr.

At the "Cool Like You: Gov Private Sector Envy" (#COOLGOV) panel at this year's SXSW, Julio Gonzalez of Open Austin noted that this crisis of confidence can directly damage efforts to fund open government initiatives. "Don’t submerge the public investment,” he said, citing the percentage of Americans who don't think of services like Medicare as government entities. "It’s important for people to know when civic data platforms are public programs paid with public dollars," he added.

Among the many civic hackers I've met and chatted with over the past month — the policy wonks, data hackers, IT managers, civic-minded app developers, data journalists and civic-minded designers who populate the flourishing community — I've observed a recurring set of intertwined challenges, articulated in different ways depending on the speaker:

- How can these efforts more effectively create citizen engagement?

- How do the privileged individuals who largely comprise the community connect with and empower those from different racial, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds, and ensure that these efforts address social inequality rather than perpetuate it?

- How do you energize, inspire, and include the many citizens who consider all government institutions to be ineffective, corrupt, and irrevocably broken?

As with all questions of governance, civic engagement, and social justice, there are no easy answers. But addressing them will require a more diverse representation of citizens, people who can hack at much more than just civic data and code. The hacker ethos must be applied to community outreach, grassroots organizing, public policy, and how we tell and understand the stories of our cities.

“Ask not what your city can do for you. Ask what you can do for your city.”

An inclusive definition of "hacker" informs the Code for America Brigade, announced by CfA founder Jennifer Pahlka during her SXSW 2012 keynote speech, "Coding the Next Chapter of American History." The Brigade builds upon the momentum established during Code Across America, a hackathon for the public good held in cities across the country on February 25.

In CfA's words:

The Code for America Brigade is an organizing force for a growing community of civic minded developers, designers, data scientists, and community leaders who will contribute their talents towards addressing the problems we see everyday. The technology that we’ll develop together and deploy locally will form a new Civic Web.

Visual notes of @pahlkadot's #SXSW keynote by @imagethink. #opengov #gov20#SXSWi twitter.com/digiphile/stat…

— Alex Howard (@digiphile) March 13, 2012

During the #coolgov panel, Kevin Curry, Program Director of the CfA Brigade, spoke about its goal to establish “hacking as a civic duty,” defining “hacking” as more than banging out code and diving into data, but rather a mentality that can be applied to any level of civic action. "Ask not what your city can do for you," he said, evoking JFK. "Ask what you can do for your city." CfA is looking for more than data scientists and Python developers to volunteer for their respective city’s chapter, though those skills are certainly needed. They’re looking for anyone with the skills and the desire to hack the civic process.

Broadening the Coalition: Addressing Social Inequality Through Open Government

The need to diversify the open government and civic data movement was emphasized by Gonzalez during the panel. Noting that “it’s a very technocratic scene right now,” Gonzalez stated that the existing communities must “broaden the coalition” of citizens involved in these efforts, to better address social justice issues surrounding race, class and the digital divide. He stressed the need to partner with community outreach organizations, data journalists, and the administrative city workers “who live in an Excel world rather than a PHP world.”

Context is Key: Who Do Crime Maps and Civic Apps Serve?

Diversifying this "very technocratic scene" is essential: civic datasets tell stories, and when not properly contextualized, those stories can do more harm than good. Infographics and data visualizations can only serve the public good if they provide the proper context. Otherwise, they risk perpetuating existing prejudices, further marginalizing disenfranchised groups.

Crime maps are an increasingly common target of critique: since police report datasets are often relatively accessible and regularly updated, crime map overlays are often the earliest civic apps to appear in a city. Speaking of the dangers of decontextualized data in a February interview, Chicago CfA fellow Ben Sheldon said to me, “we can’t just keep putting out crime maps…You have to ask, ‘how is the media framing the data, and how can the community contextualize it itself?’

Stamen founder and creative director Eric Rodenbeck aired a related set of concerns when he spoke at the first Big Data for the Public Good seminar in January. The design team behind the next-level crime map apps Oakland Crimespotting and San Francisco Crimespotting (along with a host of other innovative interactive maps and civic data visualizations,) Rodenbeck emphasized that context must be a key design component when building civic data apps, stating that "narrative is critical" and warning that there's a danger of apps and visualizations spreading and perpetuating misconceptions due to unshared cultural contexts between the people building them and the people using them.

Big Data for the Public Good | Seminar 1: Data Visualization | Eric Rodenbeck from Code for America on Vimeo.

The question of who is being served by these apps was also raised by Jake Porway during his talk at the second CfA Big Data for the Public Good seminar on Monday, March 19th. Noting that in the age of the mobile web, "everything creates data," the founder of Data Without Borders and data scientist for The New York Times emphasized that we must "leverage this data to serve more groups than the people building the apps." In other words, more apps for social justice, less bar finders for hip urbanites.

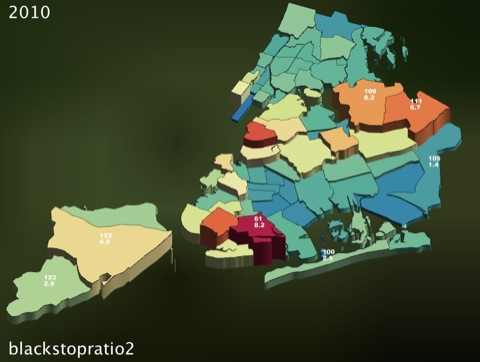

As a counterexample, Porway pointed to the work Data Without Borders has done with the New York Civil Liberties Union to map racial profiling by the New York Police Department. By analyzing data on "stop-and-frisk" incidents committed by the NYPD in 2010, they were able to map clear trends of profiling across race and socioeconomic lines. Speaking to the data scientists in the room, Porway emphasized that while doing this may seem elementary to them, the implications are transformative for social justice organizations who often lack the money, technology, and skilled staff to do such analysis. "This is about more than maps and visualizations," Porway said. "This is about empowering these organizations."

Ratio of racial composition by census tract and precinct – Data Without Borders/NYCLU.

Spatial clustering of incident counts by precinct – Data Without Borders/NYCLU.

To provide much-needed insight and context to the torrential influx of real-time data, the community of civic hackers must diversify on many fronts: as Porway urged in his talk, the sphere needs more data scientists to volunteer their efforts and apply scientific rigor to deep data dives. Meanwhile, social justice organizations have enormous caches of valuable data but neither the staff nor technical resources to leverage them.

It also requires connecting with the people and groups who are concurrently addressing these issues at the ground level. Both data journalists and hardened beat reporters who have an intrinsic understanding of a neighborhood could provide skill sets, knowledge and critical approaches others may not bring to the table. And there also needs to be a place at the table for emergent organizations and movements that are addressing related issues on a grassroots level, such as Occupy Research and Chicago's Read/Write Library.

It's All Data: "Community is not read-only, and it already has a voice"

Read/Write Library is a Chicago-based organization and space that aims to serve as "an all-inclusive collection of Chicago-specific media, produced by and for the community." During her talk at SXSW, founder Nell Taylor advocated for a radical rethinking of the role and relative value of both print and online media. Read/Write Library considers zines, vanity publications, poetry chapbooks, art books, community newspapers and many other materials to be data worthy of being archived.

"Community is not read-only, and it already has a voice," she told a room of attendees of SXSW Interactive, stating that "we need to change the cultural context so we rethink what is worth keeping. "People already have a voice," she said, adding that disenfranchised communities in particular have a long history of self-publishing. The marginalized voices who have traditionally expressed themselves through self-publication add new layers to the cultural and socioeconomic map of a city's history when archived and viewed in aggregate. Otherwise, the small-scale publications the library has collected over the past five years risk becoming data exhaust, a danger Porway warned against in his talk.

In the case of the Read/Write Library, the collection of the materials is often done in the field, and relies on building networks and egalitarian relationships with socioeconomically diverse groups offline and on. They call this process of collection "controlled crowdsourcing," through which they actively seek out contributions from the community.

Once archived, this physical data can be leveraged by to introduce, in Taylor's words, "a cultural layer to civic technology." The Read/Write Library is aiming to fill in the socioeconomic gaps in Chicago's cultural memory in part by collaborating with members of the city's vibrant open government and data hacker communities. Taylor said, "The questions we're asking are: how do you get this data into a mappable flow? How do you connect this print material with apps that are being built in hackathons?" To this end, the Library's existing space will double as a hackerspace in the months and years ahead, to serve as a nonprofit space that facilitates the sort of serendipitous connections and diverse collaborations that Code for America, Gonzalez, and Porway have articulated the need for.

The Beginning, Not The Finish Line

Photo by Marc Buehler on Flickr.

This post is an embryonic, discursive attempt to encapsulate many of the disparate but related conversations I've heard and taken part in during the past few month; not so much a call to arms as a call for conversation and connections that could lead to new collaborations between disparate groups.

In his Monday talk, Porway articulated a number of related issues, noting that "data and skills have been silo'd from one another" and that the "top-down world of big silos is breaking down to a bottom-up world where we're nodes in a connected society."

Code for America Brigade, Data Without Borders, the Read/Write Library, and a number of other nascent projects are pointing the way to potential models for diversifying the community, increasing engagement, and making civic data efforts better represent and serve the communities they hope to help.

But bridging cultural and socioeconomic gaps to create a more diverse, representative community of civic hackers who can more richly contextualize the data is merely the next step. The beginning, not the finish line.

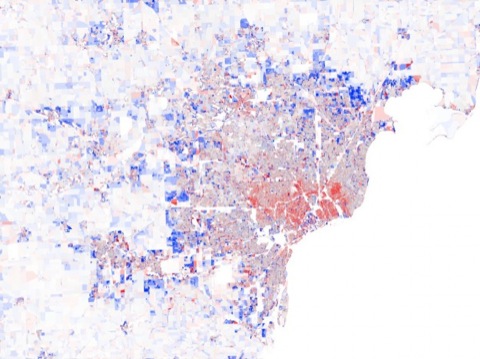

Detroit population change, 2000-2010. Visualization of Census data by Stephen Von Worley at DataPointed.

To build resilient, peer-to-peer cities the precarious economic times demand, these conversations and collaborations need to be facilitated top-down, ground-up, and between every other decentralized community node that can contribute to weaving a diverse tapestry of a city's political, cultural, historical, and socioeconomic data. This vision was perhaps best encapsulated by Howard during the SXSW panel he moderated, "Shaping Future Cities with Mobile Data". Storified on his blog at govfresh, Howard envisioned "a future of cities fueled by citizens, open data and collaborative consumption."

I find this vision, and the ongoing convergence of these disparate groups, immensely inspiring. I want to help facilitate this conversation in the weeks and months ahead, here on Shareable, on Twitter, and elsewhere. I've joined the Austin chapter of the CfA Brigade, despite my limited coding knowledge, to see what connections, skills, and contexts I can contribute to the city's open data community, play a role in facilitating these conversations in the city, learn more coding skills, and most importantly, hopefully give back to the city. I'll be documenting this learning process and drawing connections I observe in a series of upcoming posts on Shareable.

To those of us who don't think of ourselves as hackers but find ourselves applying that ethos to other trades — journalists, community organizers, field researchers, social justice activists, lawyers and policy wonks, and many more groups — let's join the conversation, contribute our skills to the civic hacker community, and see what we can build together for our cities.

——————————————

Download "Hacking as a Civic Duty" as a free eBook: