This much is certain: Our society would benefit immensely if we can find ways to share our homes and all the things inside. In theory, there is also great potential to make money from sharing our tools, equipment, homes, and cars. But each time we devise a way to profit from sharing, we may trip over the following legal paradox: our zoning laws are designed to prevent us from turning our home into a place of business.

Un-Shareable Cities

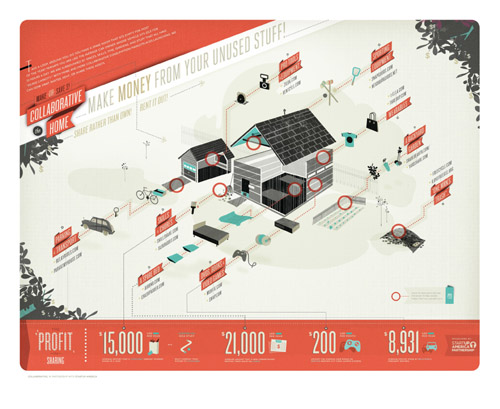

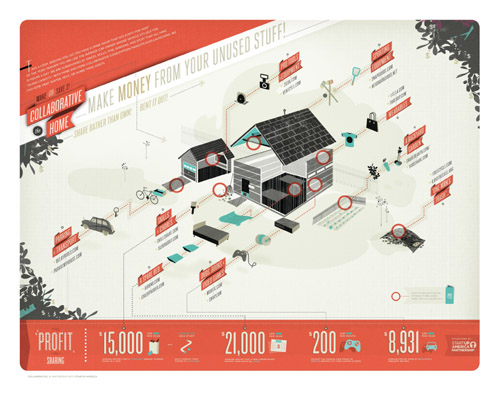

Single-family residential zones lay the groundwork for a disconnected society, where we are encouraged to live in isolated and independent boxes. There are strict limitations on our abilities to operate businesses on residential properties. That’s why the lawyer in me worries when I see this graphic:

The Collaborative Home as drawn by Collaborative Consumption. Used under Creative Commons license.

It looks like your average suburban home; yet, it’s the center of a lucrative rental business, where you can apparently profit from sharing everything from household goods to the home itself. It’s probable that everyone could get away with a little money-generating sharing here and there, and sharing is really a great thing to do, for many more reasons than the money. But when your driveway starts to look like a rental car lot, and your home looks like a bed and breakfast, and your front door becomes a hub for tool and equipment rentals, your neighbors and/or your local Planning Department might start to ask questions.

Case in point: Airbnb

As it turns out, you can’t just turn your home into a hotel. This legal reality has, lately, been pointed out to collaborative consumption pioneer Airbnb and its customers. Last week, we read about it on CBS: San Francisco Law Prohibits Short Term Rentals Popularized By Airbnb, and in the San Francisco Chronicle: Airbnb, Rivals May Face Challenges over Rentals.

The thing I love about Airbnb is that it’s a peer-to-peer alternative to our dependence on chain hotels. Airbnb has spurred millions of people to open up their homes to strangers. Travelers have a range of options: stay on someone’s living room futon for $15 per night or get a luxurious home all to yourself for $600 per night. Some hosts can make serious money offering home stays and rentals on Airbnb. According to the folks at CollaborativeConsumption.com, $21,000 is the annual amount earned by the average Airbnb host in New York. Impressive. Legal constraints aside, Airbnb could actually achieve the miracle of making it affordable to live and stay in New York City. And it is the residents, not international hotel chains, that profit from the city’s tourism and visitors.

How to Accidentally Become a Hotel

In San Francisco, you can accidentally become an illegal hotel simply by charging a guest for a short-term stay, defined as fewer than 32 days. It’s that simple.

Technically, you COULD turn your home into a legal bed and breakfast, if you are able to jump through a series of expensive legal hoops. For example, in San Francisco, that would require that you:

-

Obtain an expensive conditional use permit from the Planning Department; this will be difficult or impossible, by the way;

-

Pay the 15.5% hotel tax on your gross income from guests;

-

Pay the annual $999 food preparation license fee, so that you can serve breakfast;

-

Demonstrate your compliance with a long list of safety laws, such as prohibiting cigarette smoking, posting exit signs, adhering to heightened fire codes, not offering a shared hand towel, etc.

San Francisco boasts some of the highest rental prices in the country. Photo credit: Jon Zander. Used under Creative Commons license.

All that so that you can get a few bucks from your house guests!? In sum, San Francisco leaves almost no legal room for people to offset their housing cost by sharing with travelers.

On one hand, San Francisco rightly worries that vacation rentals could replace the already sparse supply of residential rental units. San Francisco would probably also like to preserve, where possible, the quiet residential nature of some neighborhoods, rather than enabling a series of out-of-town guests to cycle through. And, of course, no one wants to make the neighborhood parking situations even worse than they are.

But I would ask San Francisco: shouldn’t you also be worried about the fact that tenants sometimes burn up to 70% of their incomes on rent? In addition, it’s next to impossible to find an affordable hotel. In such an expensive city, it seems like a good opportunity to put two and two together, and come up with a more sensitive and shareable law.

A More Shareable Law

Changing the law does not need to result in opening the flood gates to an unrestrained operation of hotels. Plus, with the hefty hotel tax, it could even be a source of income for the city. Why not enable residents to have paid houseguests for a limited number of days per year? Or the city could cap the gross income that a household could generate from guests at, say, no more than 25% of the unit’s cost. This is in recognition that the purpose of sharing is not necessarily to profit, but, rather, to offset the cost of housing.

As a general rule, I believe that we should carve out the legal space for income-generating activities when they:

-

Happen at a very small scale,

-

Incur very little risk,

-

Occur for the purpose of off-setting the cost of living, as opposed to making a profit,

-

Involve a pre-existing relationship between the producer and consumer, and/or

-

Benefit the public/contribute to local economic stability.

Enabling short-term, paid home stays is a perfect example of an activity we should make legal space for.

The table is set for guests to arrive. Photo credit: Lachlan Donald. Used under Creative Commons license.

The Sharing Economy Reclaims “Accessory Use”

Even without changing the laws, there’s room to argue that we have a right to share. “Accessory use” is a term that we should all get comfortable with, since it’s a window to arguing that we have a protected right to engage in certain sharing activities. “Accessory use” is a zoning term that, in the residential context, refers to the ways that we customarily and incidentally make use of our homes. For example, there is rarely anything in our zoning ordinances that explicitly allows us to have visitors, but our right to do so is protected by the fact that such an activity is a customary use of our home. Sharing, generally, is an accessory use. Having a dinner party, having a houseguest, lending a tool to your neighbor – these are natural and customary things we all do as part of making a home.

In addition to being customary, an accessory use must be incidental to the primary use of the property as a home. The activity of receiving visitors should never become so frequent or large in scale that it overtakes the primary residential use. Furthermore, having visitors must be related to one’s own residential use of the property. There are many court cases that examine what is or is not related, incidental, customary, and so on. For example, in a 1958 New York case, Facci v. City of Schenectady, a homeowner was denied the ability to park a commercial vehicle at his house, since parking the vehicle was not related to his residential use of the property. At the same time, it might have been fine for that vehicle to park there if the driver were there for a social visit, which is related to the residential use. That’s just one example of the way courts think about the issue.

Having social guests is related to a resident’s enjoyment of the home. But what about having a series of total strangers pay to rent your room – is that an accessory use? Maybe, if you could argue that meeting total strangers is your personal hobby (This is true of many couchsurfers.), or if you could argue that providing a room to total strangers is a customary use of a home.

It’s worth a try. I have to imagine that the sharing movement will be aided, somewhat, by the fact that definitions of accessory use developed during times when people really did share a lot more. After all, where DID travelers stay in the days before hotels? With other people! And the other people, in many cases, probably asked for some form of compensation.

Generally, it would be fun to comb through accessory use cases to determine how various sharing activities fit in. But with or without the accessory use argument, it would not be a stretch for any city to step up and explicitly recognize our rights to have occasional paid guests. It would be a nice step toward re-introducing sharing into the fabric of our communities, which all cities should make a priority.