When his car died in 2007, Shelby Clark put off purchasing a replacement. He spent time researching his options and looking for a good deal. In the interval, he signed up for the car-sharing service Zipcar and began taking more public transportation. A year passed and, as it happened, he never got around to owning another vehicle.

At the time, Clark was working as Director of Kiva.org in San Francisco. In 2008, he moved to Cambridge, now a dedicated Zipcar member, and began his MBA at Harvard Business School.

Then on a frigid, blustery day in November 2008, Clark needed a car, but the closest one was parked a distance away:

For all of the money-saving, hassle-free perks that Zipcar offered, accessibility was still an issue.

“As I was biking nearly two miles through snow and sleet to get to my Zipcar,” he recalls, “I passed hundreds of cars on the road that had clearly not been driven for weeks, and that was when the light bulb went on. I thought: ‘Wait a minute! I should be taking one of those cars!’”

Clark began planning just after that incident. He researched insurance and technologies, and surveyed the marketplace to see if there were other people who want and need to their share cars—and would be open to doing so with complete strangers.

In April 2009, Clark founded RelayRides, the first person-to-person car-sharing service, which will be launching soon in Baltimore. Unlike fleet-based services—Zipcar, City CarShare, I-GO, and others—which maintain their own vehicles, RelayRides relies on individual car owners to supply the vehicles that other members will rent.

In April 2009, Clark founded RelayRides, the first person-to-person car-sharing service, which will be launching soon in Baltimore. Unlike fleet-based services—Zipcar, City CarShare, I-GO, and others—which maintain their own vehicles, RelayRides relies on individual car owners to supply the vehicles that other members will rent.

Clark estimates that car owners will be able to make between $2,000-$8,000 per year, depending on the desirability of the vehicle and how often it’s made available for other members to use. (RelayRides’ cut is 15% of the rental fee.) Essentially, car owners will be able to monetize an asset that simply sits around for all but a couple hours out of everyday. It may also help take more individual cars off the road, one of the most important ways to address global warming.

“After 8 years, car-sharing has only achieved roughly 10,000 vehicles and fewer than half a million members; that’s really not very many,” says Sunil Paul, an investor and entrepreneur with Spring Ventures. “In order to make this a much more scalable, ubiquitous phenomenon across the United States, there has to be a better solution than what’s being pursued today—and we believe that car cost-sharing is a big piece of that solution.”

Peer-to-Peer vs. the Zipcar Experience

The sudden ability to make money from one’s car is new and enticing, suggested Clark’s research—what’s more, RelayRides allows owners to price their own vehicles for rent.

“Owners are able to specify when the car is available, where it’s available, as well as the price of the car, which we help to provide guidance on," explains Clark. "It’s really a marketplace." And because RelayRides can eliminate the overhead costs for ownership and maintenance of automobiles, they hope to offer more competitive pricing for renters than traditional car-sharing programs.

From the renter’s standpoint, RelayRides alters little else about the more conventional “Zipcar” experience; an individual signs up and, if approved, receives a smartcard. She can then find and reserve cars online with gas and insurance included in the rates. From there, the renter can access a designated car at her booking time using the smartcard. (RelayRides arranges for a certified mechanic to install the complementary sensor device on owners’ cars.)

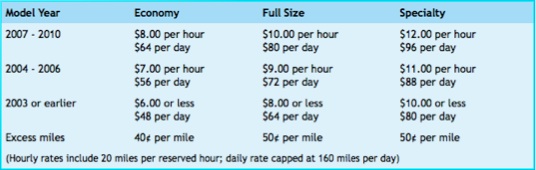

Relay Rides’ suggested rental fees for owners, available at relayrides.com

Relay Rides’ suggested rental fees for owners, available at relayrides.com

The Trust Factor

Peer-to-peer car-sharing within closed networks (friends, family, neighborhoods) is already a successful reality with services like Divvycar. (Its parent, Divvy, is an integrated reservation and billing system for sharing any asset within a chosen community.)

The notion of opening up one’s sharing network to just about anyone places car owners in a potentially precarious situation. Nevertheless, RelayRides has received positive response thus far—especially from car owners.

“There’s certainly a segment of car owners that would never do this,” says Clark (pictured left). “Then there is a substantial group of people who may be a little caught off guard when they first hear about the idea—Wait a minute, you want me to let a stranger rent my car? That’s crazy!—but when they think about it a little more, and it actually makes a lot of sense.”

“There’s certainly a segment of car owners that would never do this,” says Clark (pictured left). “Then there is a substantial group of people who may be a little caught off guard when they first hear about the idea—Wait a minute, you want me to let a stranger rent my car? That’s crazy!—but when they think about it a little more, and it actually makes a lot of sense.”

For those who may feel less laissez-faire about lending, Divvy is a low-cost, low-tech solution that’s not nationally marketed; essentially, individuals make their assets available to an affinity group—a well-regulated network—where there’s a strong sense of affiliation and social accountability.

Divvy founder and CEO Aaron Freed has concerns that, under more open circumstances, the trust factor could undermine RelayRides’ efforts: “Not to be the Debbie Downer, but this model is asking people to contribute their vehicles to a pool that’s been marketed and available nationwide and I think that, for Americans particularly and for people in general, trust is a very important element of sharing. I don’t necessarily value the dollar so much that I want complete strangers availing themselves of whatever it is that I own, especially my car.”

But RelayRides has adopted a number of measures to facilitate trust between strangers. In addition to screening the driving records of all potential renters, the company will implement a two-way review system (much like eBay); car owners will be able to review renters, and renters will be able to rate cars they’ve driven. RelayRides will allow car owners to screen out drivers that don’t meet their rating criteria (much like Prosper). The hope is to reward both respectful treatment of others’ property and quality upkeep of vehicles by their owners.

But even with features designed to heighten transparency and accountability within RelayRides’ community, Clark is relying largely on the emergent values of community, indirect reciprocity, and access instead of ownership—all of which are especially prevalent in today’s Web culture—to engage potential members and regulate conduct in a peer-to-peer sharing environment. Not surprisingly, young urban professionals are one of RelayRides’ target demographics. They also expect to hold appeal for “1.5 car families”—families who always need one car, and just sometimes need a second vehicle.

Sunil Paul (left), a Bay Area investor and entrepreneur (formerly of Brightmail), suggests the secret might be to reframe car-sharing as cost-sharing. “I like the term ‘car cost-sharing’ because it better explains the idea that this car-sharing is not like existing car-sharing organizations—this is really individuals deciding that they want to make their car available to their trusted networks of friends—of neighbors, family—and that’s sort of a different way of thinking about the opportunity.”

Sunil Paul (left), a Bay Area investor and entrepreneur (formerly of Brightmail), suggests the secret might be to reframe car-sharing as cost-sharing. “I like the term ‘car cost-sharing’ because it better explains the idea that this car-sharing is not like existing car-sharing organizations—this is really individuals deciding that they want to make their car available to their trusted networks of friends—of neighbors, family—and that’s sort of a different way of thinking about the opportunity.”

What About Insurance?

Of course, car owners aren’t the only faction with concerns about sharing amongst strangers—insurance companies care about that as well.

“The insurance barrier is an important one. Insurers are inherently risk-averse, and commercial lines and private lines have very different mentalities,” explains Freed. That’s why Divvycar is designed for sharing within tight-knit communities (like condominiums, churches, or small companies), where people already know and trust others in their network.

There are even laws that forbid policyholders from making money off of lending their vehicles, which has prevented broad-scale, peer-to-peer auto-sharing.

But insurance concerns haven’t proven an insurmountable barrier for RelayRides. “The car owner maintains his existing insurance policy, and then we provide a $1 million insurance policy in addition to that, which covers the car owner, the car renter, and RelayRides,” says Clark.

Freed is watching RelayRides’ innovations. “I'm emboldened and excited that [others in this space] are going to try to crack the code,” he says.

Peer-to-Peer Possibilities

So why are peer-to-peer car-sharing services emerging now?

Part of the answer might lie in the way online and offline services like Zipcar, Prosper, Netflix, and Kiva.org are training us to share our stuff—people are simply getting used to the idea. “‘Zip’ has become a verb to the point that we could ‘zip’ anything—they just happened to start it with cars. Close on their heels was Avelle (formerly Bag, Borrow Or Steal) and now SmartBike for bikes on demand. The next step seems to be a crowd-sourced version of Zipcar,” says Freed.

Another part of the answer might be found in our response to the ecological and economic crises Americans are facing. As Clark explains, “You just think of the number of cars on the road, and the resource that we have in our own communities is so massive… what the peer-to-peer model does is it really allows us to leverage that instead of starting from scratch and building our own fleet.”

From an individual’s perspective, peer-to-peer sharing is a means for owners to monetize their assets during times when they don’t require access to them. But peer-to-peer models can also be understood to utilize existing resources more efficiently—ultimately, to reduce the number of cars on the road—through shifted mentalities about ownership, the intelligent organization of information and, increasingly, through real-time technologies.

From an individual’s perspective, peer-to-peer sharing is a means for owners to monetize their assets during times when they don’t require access to them. But peer-to-peer models can also be understood to utilize existing resources more efficiently—ultimately, to reduce the number of cars on the road—through shifted mentalities about ownership, the intelligent organization of information and, increasingly, through real-time technologies.

Since peer-based car-sharing companies don’t bear the overhead costs of owning and maintaining their own fleets, they don’t require the high utilization rates for vehicles that Zipcar and similar programs do—the result is comparatively fewer limitations for the size and scale of peer-to-peer operations.

For renters, this can mean a considerable difference in convenience and vehicle accessibility; for people like Clark, it can mean the difference between a miserable 2-mile trudge in snowy weather—or an easy stroll—to retrieve a rented car.

(Currently, Divvycar offers a solution for communities who have difficulty accessing shared vehicles in locations convenient to them, since Zipcar’s model can’t accommodate user demand very flexibly. Building developers can request a Divvycar as a community vehicle, which earns them a LEED certification point and, in many locations, allows them to forego the building of several parking spaces—which can mean upwards of $100k in savings for a developer. Just earlier this month, Zipcar announced that they will work more closely with building developers in San Francisco to this end.)

Person-to-person car-sharing may also be emerging because mobile technologies are making it more convenient, providing the ability to gauge user need, crowd-source available assets, and fulfill requests more flexibly and intelligently—by location and in real-time. The Taxi Magic iPhone app, for example, allows users to summon a cab with the push of a button. Applied to ride-sharing, this type of real-time mobile technology could have broad implications for when and how people opt to share. (How many people would rather share a ride than pay for a cab, provided both were readily available?)

Sunil Paul is exploring the convergence of technology and peer-to-peer car-sharing in his own endeavors, with an eye toward the urban future: “Because of what’s possible with smartphones and information technology within the car, as well as embedded new technology that’s going to be built into cities themselves—it’s really transforming transportation in a way that hasn’t happened since the automobile was created in the first place. We are taking advantage of new technologies—especially smartphone technologies—to deploy and create new forms of transportation, and make existing forms of transportation more convenient.”

For many people, sharing is about reducing transactional burden—removing costs and unnecessary hassle by accessing just what they need, when and where they need it. As RelayRides and other peer-to-peer services begin to demonstrate material benefits for members of truly open and scalable systems, we can expect to see a new psychology—and allure—to sharing emerge. This has the potential to change how we mobilize, consume, socialize—ultimately, how we live and function together as a society.

“When we first started working on this idea, a lot of people thought we were nuts,” says Clark, “‘Nobody is going to rent out their car!’ And we’ve proven them wrong. It’s a major shift—it’s moving from a ‘mine’ to an ‘ours’ mentality. There are lots of skeptics, but if we can find ways to come together and use resources efficiently, then everybody wins.”