John Wilson stopped in Chicago during a road trip from Boston. He was walking by Wicker Park when he noticed a “totally anonymous and unsupervised” local drop box where you could leave or take unwanted books and DVD’s.

When he got back home, he started talking about the idea with Chris Maggio, an old school friend and co-founder of the art collective the Future Machine. Would something similar work in Boston? They decided to find out.

Anthropologists and socio-economists have spent decades examining the principle of people responding to a positive action with another positive action, commonly referred to as “direct reciprocity.”

The roots of “reciprocity” are indeed re and pro, meaning back and forth, to and fro between people. The well-known phrase “You scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours” might sound cynical; another, “Do unto others as they do unto you,” sounds more idealistic—but both capture the belief that humans have an innate propensity to reciprocate because we understand that it is in our long-term self-interest to do so.

This idea of reciprocation explains how cooperation worked in times when transactions took place between relatives, neighbors, or members of the same small village—the exchanges were face-to-face, and a person could easily keep track of interactions and the reputations of villagers.

But what happens in urban communities where the giving and taking is happening amongst lots of people who don’t know one another and—as is the case with sharing over virtual networks—are geographically dispersed? In other words, what human forces are at play when the reciprocation becomes indirect?

Inspired by that drop box in Wicker Park, John Wilson and Chris Maggio decided to launch an experiment in “indirect reciprocity” they called the Stranger Exchange.

Both artists have long been fascinated by open systems built on the philosophy of “Have a Penny, leave a Penny. Need a Penny, take a Penny,” such as Wikipedia and Craigslist, or The Free Shop in New York City. As with the Wicker Park boxes, they would try to create a dialogue between strangers and exchangers. But there would be two key differences from the boxes Chris had originally seen in Chicago: they would “broaden the scope of what could be dropped” and they would build a simple online “guest book” so that people could share messages about things left and received.

They discussed a few locations for the first box in Boston and decided on a spot just outside the popular 1369 Coffee House in Central Square, in Cambridge. As Chris says, “It really is a meeting place, a hub for transportation and where a diverse range of people pass through: families, students, professors, local residents, working class, blue collar etc.—so a good Petri dish for the idea.”

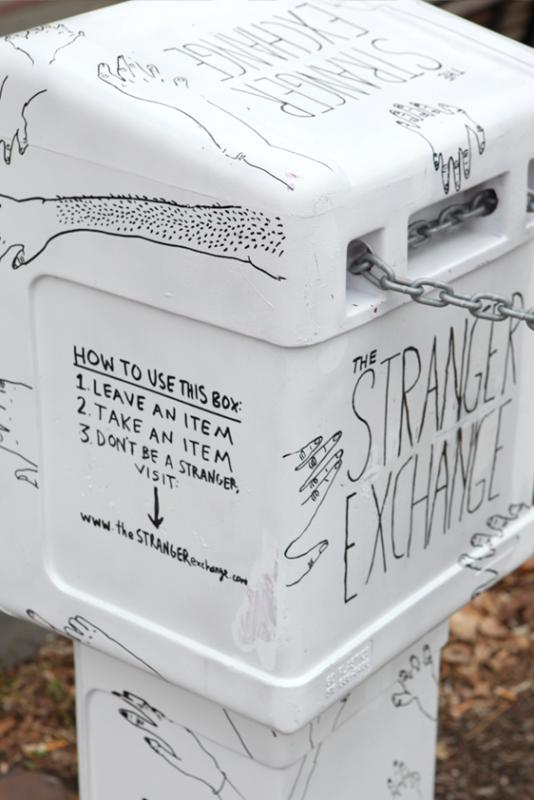

Next they found an abandoned newspaper box, and with their friend Samantha repurposed it as the first local "drop box." They wanted the box to stand out enough to be noticed—but they didn’t want it seem at all “kitschy” or “contrived.” It was also critical that it feel anonymous, so that the community would immediately see the box as “theirs” and not as the possession of whomever put it there.

They painted it white and scribbled simple instructions on "How to use this box" on the side:

They painted it white and scribbled simple instructions on "How to use this box" on the side:

- Leave an item;

- Take an Item; and

- Don’t be a Stranger.

In black felt tip pen, they drew arms reaching from the instructions to the handle in the center of the box, inviting participation. On the front opaque window, John and Chris also posted a few suggestions on items to leave, such as books, movies, old pictures, and even self-portraits or rumors. But for the most part, they wanted to let the users define what was appropriate to deposit.

They placed the Stranger Exchange box in Central Square during the late evening of October 25, 2009. Since then, either John or Chris tries to visit it every other day to see what has been left and taken. They’ve discovered books like A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, as well as movies, photographs, souvenirs, and even letters.

But what really has surprised the friends the most is the quality—and, in many instances, the effort—that has gone into some of the things that have been deposited. Plus, people are clearly making items specifically, for the box for no other reason than to share.

For example, one person left a beautifully drawn sketch of a footbridge with a note at the bottom: “Sorry I could not finish, ran out of ink.” Another example: drop boxer user “Mish” wrote on the online Stranger Exchange guest book on October 30th: “Found a dope mix CD in central’s box, so I mixed one myself and dropped it off today. Enjoy to the lucky.” It included a URL to a picture of the CD that Mish had carefully illustrated with sky drawing.

“I still think people fundamentally like giving to someone they don’t know and finding ways to help each other,” says Chris.

Interestingly, the early "members" of the Stranger Exchange seem be participating for similar intrinsic motivations that are fueling the open peer-to-peer movements such as Flickr, Wikipedia, BitTorrent, BePress and so on. For these systems to keep flourishing, people need to “give before they get,” a dynamic that is built on a new kind of trust, trust in people you don’t know or are not even friends with.

This in turn reinforces certain behaviors—collaboration, kindness, openness and honor—that are critical for sharing to happen between strangers. What’s interesting is that once people participate in these exchanges, they experience the proverbial "warm inner glow" and they crave that experience again. In other words, the altruistic action and indirect reciprocity becomes self-reinforcing.

So far not one piece of trash has been left in the Stranger Exchange. “There is this unexpected curiosity and respect for something like this,” says John. “I am not sure where it comes from. Perhaps people value things made with care and honor systems built on trust?”

So far not one piece of trash has been left in the Stranger Exchange. “There is this unexpected curiosity and respect for something like this,” says John. “I am not sure where it comes from. Perhaps people value things made with care and honor systems built on trust?”

In fact, both believe that if the box had a logo on the side (or was even run by the city) some of the respect and trust for it would deteriorate “The relationship becomes too big,” says Chris.

In this sense, the Stranger Exchange is a hyper-local Craiglist or Freecycle, following the notion of “of the people, by the people, for the people” that exists in so many sharing networks we are seeing emerge and scale. It will be fascinating to see how the Stranger Exchange plays out over time. John and Chris already have two more boxes at the ready that they plan to drop in different areas of Boston. Their hope is the idea will eventually spread around the world.

Rachel was first introduced to The Stranger Exchange by Kim Gaskins, a Boston blogger for Latitude, who spotted the box in its first week.