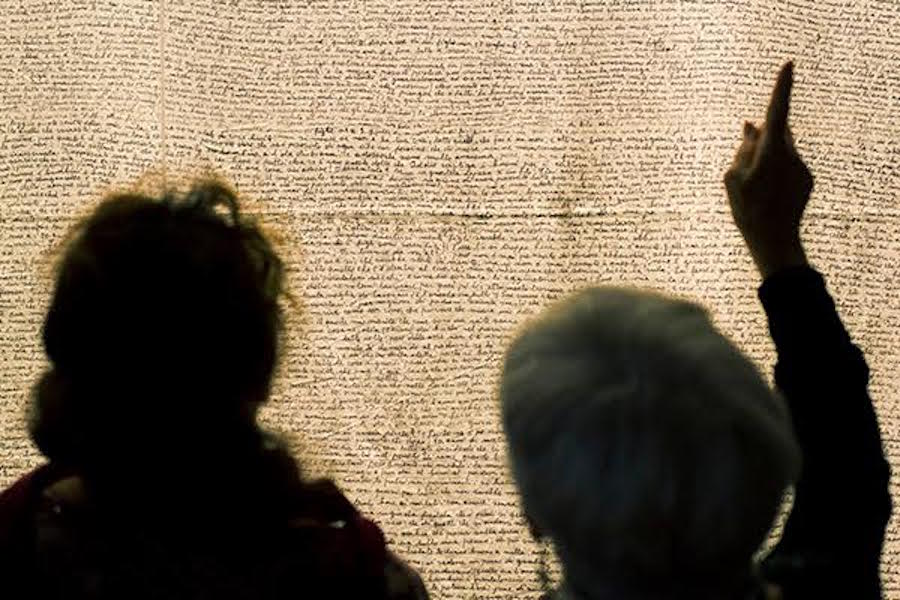

The Archive is home to deeply touching personal works, including this autobiography written on a bedsheet. Photo: Samuel Webster

The Fondazione Archivio Diaristico Nazionale (National Diary Archive Foundation) is an award-winning public archive in the small Tuscan town of Pieve Santo Stefano. The Archive collects the diaries, letters and autobiographical memories of ordinary people. The Archive, and its adjacent museum, brilliantly illuminates a revealing slice of the history of Italy and its people. It has collected over 7,500 stories that cross local and national borders. The universal power of stories and the bottom up approach to culture and knowledge building, together with the "glocal" aspect of the Archive, makes it one of the world's most innovative archives.

When I was first introduced to the Fondazione Archivio Diaristico Nazionale, it felt natural to volunteer at this small, yet incredibly meaningful project. I never imagined, back then, that a cultural institution in my tiny Tuscan town would become a life-changing spot for so many people, including myself. I recently sat down with Natalia Cangi and Loretta Veri, the Archive’s director and fundraiser, to learn more about the project's origins and what makes it special.

Alessia Clusini: What did the project’s founder, Saverio Tutino, originally envision for the National Archive of Diaries?

Natalia Cangi: The original idea consists of giving a home to common people’s stories, by creating a memory archive where all people have the chance to send in a trace of their own lives. Saverio Tutino decided to create a very democratic place where ordinary folk have a special spot.

How did he start this personal story collection and how does the team keep it going?

NC: Together with the idea of the Archive was born Premio Pieve (Pieve Prize), a national contest Saverio launched to choose the “best” (we can’t actually talk about the absolute best, because all the stories are extremely important) within the autobiographies, diaries, letters collections and memoirs that people would send to the Archive.

In this way, he thought it would be easier to convince people to donate and share their own personal stories in a public space with a vast audience. So Premio Pieve was the first form of propeller for personal story sharing within an audience that wasn’t used to it.

Back in 1984, before the blogging and social media boom, sharing personal lives and content wasn’t such a mainstream phenomena. An onset of awareness was needed within the common people—not writers or professionals in cultural fields—in order to share parts of their lives or those of their relatives. Today, Premio Pieve remains the most important incentive for people to send their memories to the Archive. Year after year, it’s a sort of public piazza where the stories come to life again, and many people come from all over the world to see it. The team works hard to communicate and logistically manage the memory, both online and offline.

Archive director Natalia Cangi displays one of the pieces from the collection. Photo: Antonella Brandizzi

What makes Saverio Tutino a pioneer of the bottom-up approach to knowledge and cultural heritage?

NC: Tutino’s archive idea has a lot of political value in itself: he wanted to give a voice to those that don’t have it, telling history through common stories, in a bottom-up approach. Tutino was the one saving them from oblivion, and thinking beyond the idea of a library or a mere deposit. He used the word “vivaio” (nursery), meaning the place where new lives grow and develop. So our job—to give value to the little plants, lives, stories—consists of giving them new life, while respecting them and their authors.

Giving value to the stories means, certainly, maintaining and protecting them (we are in the Italian Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape), and besides that it means facilitating the diffusion of the Archive concept into as many fields as possible: we still do that by publishing the stories as we used to, but we also do it by investing in complex and innovative projects, such as the Impronte Digitali (Finger Prints) project, funded by Fondazione Telecom, through which we’re digitizing all the memory heritage in order to share it with a vast community and to make it live forever.

How do you keep Tutino’s vision alive while innovating the format?

NC: People and their stories are our focus, and they’ve always been our focus, many years before story hubs such as Facebook or blogs. So we naturally expanded our action online, creating a beautiful and active community, making innovative cross-media projects happen and crossing local borders.

Premio Pieve is the first Italian festival to be live tweeted both in Italian and English, with our social media team juggling the responsibility of translating, across different channels and formats, such intimate and personal stories, just as we do offline. Moreover, we keep a relationship with anybody that sends us their personal story. Our everyday activity is to keep that link, even after many years, via phone, email, and social media. Our online network, comprising unknown authors and everyday people, but also journalists, artists and culture professionals, is always in touch with the Archive.

Just as an example, last week we sent out a newsletter about Saverio’s anniversary. You have no idea how many heartbreaking email responses we got back from our community. The Archive speaks to people's hearts, and the relationship with people is not forced, but organic and tangible. It sometimes starts online, and then it shows up offline, or the other way around.

Visitors explore the archives. Photo: Samuel Webster

How is the Archive working on the “knowledge as commons” aspect?

NC: The Archive has had, since the very beginning, a very contemporary approach to content sharing, giving to the authors all the power and the rights of their stories, while preserving and communicating them. We don’t own the stories—we share the stories, when the authors want that. We tend to let the stories speak for themselves, with no critical intermediation, and we work really hard to make this culture accessible to everybody, both in the academic and non-academic world. The Archive model is open source and we welcome everybody from anywhere in the world, seven days a week, for free (group tours offered for a small fee).

What's the global power and potential of the National Archive of Diaries?

NC: The Archive is becoming an offbeat, international tourism destination because it is a really specific and unique place to find yourself. Geography doesn’t help us: we’re not on a mass market tourist trail, and infrastructures/public transport don’t make tourists’ life easy. People that love us define the trip to the Archive as a pellegrinaggio (pilgrimage).

Indeed, going on a pilgrimage means walking toward particular, unique places, extraordinary experiences. The journey to the Archive is a layperson’s pilgrimage. Those who come here can find a hub of stories that tell the last 250 years of mankind’s history. All the pieces are in Italian, yes, but because Italians migrated all over the world, the content can also be about Australia, Canada, US, Latin America, etc. It has a universal voice.

Is the Archive a scalable and repeatable model?

NC: Tutino’s dream was to see, in every little national and international city, an archive collecting common people’s memories. We believe in his vision and keep it alive. Being an inspiration for archives all over the world, we created an open source model. We facilitate and support many new archives, some just like ours, and others with differences based on local culture and needs.

“The model works,” says everybody that has started a project upon the Archive’s inspiration, whether in France, Austria, Germany, Belgium, Netherlands, Spain or Portugal. We’re now talking about it with institutions in Canada and Mexico as well. Reading history from the bottom is, for sure, a universal common need.

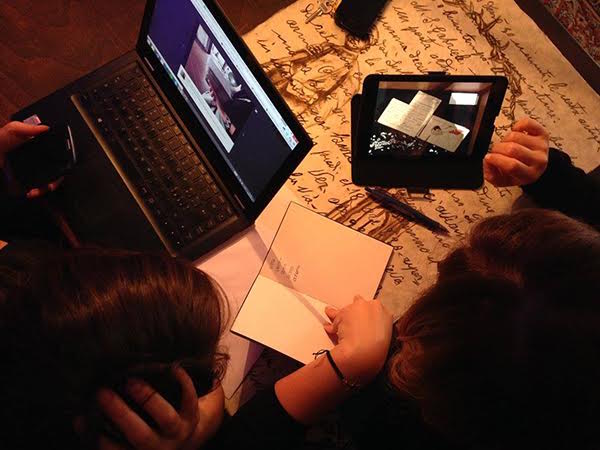

The Archives' social media team reviews mentions of their annual festival across various channels. Photo: Samuel Webster

What's the value of relationships in the everyday life and in the strategy of the Archive?

Loretta Veri: The Archive was created by its founder as a place where people could share and cultivate relationships. Today they’re trendy words, but we have been using them for more than thirty years now. Giving away your life story, your own diary, is a special gesture of donation based on trust, and it is a considerable way of sharing.

Since we started working specifically on fundraising, in March of 2010, we have enhanced our relationships. In fact, that is exactly what fundraising is all about: creating relationships, drawing a link between the benefactor and the beneficiary to support a cause.

What is happening more and more over the years is that those who give their memories to the Archive come to check out the place that has welcomed them. Thus, they get to know those who take care of their writing. Naturally, the donors often decide to stay in touch through e-mail, or handwritten letters, or phone calls. Eventually they will come back to visit the Archive, often during the days of the Prize, which some consider an unmissable appointment year after year.

Nowadays people maintain their relationship with the Archive thanks to the internet and especially to social media. Some diarists and friends of the Archive open their houses to us and become people we usually see and hear from. They simply become part of our lives.

How important is collaboration and volunteer work in the Archive activities?

LV: Volunteers are essential to our cultural institution and volunteering is, above all, our core activity. Premio Pieve simply could not exist without volunteers, including the few who get a small salary as employees or collaborators. Money left over for workers is so scarce that it would be unfair not to include everyone in the category of volunteers, even director Natalia Cangi whose salary barely covers a third of the time and commitment she spends in here.

That’s why all the people who work for the Archive call themselves volunteers, even when they get a remuneration. Volunteers do everything: they read the diaries, transcribe, catalogue and digitize them. They greet the diarists when they come to give their memories, introduce them around, and guide them to the Museum. Volunteers set up events, run the website, social media pages, newsletters. They edit books, do the fundraising and manage European projects. They also do translations, public relations, they write articles, take pictures, set up exhibitions, moderate presentations, make public readings, lead autobiographical workshops and run many other activities. To rely on such a specialized, enthusiastic, helpful and always available group is the fortune and the strength of this institution.

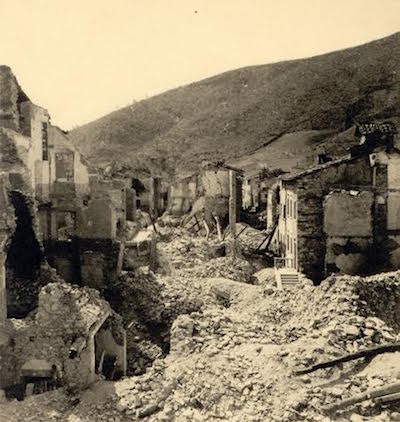

Credit: Archivio Livi. The Archive is the collective memory of a town that was 99 percent destroyed during World War II. Late in the war, the Nazis destroyed Pieve Santo Stefano and much infrastructure along the Gothic Line, their retreat route to Germany, to slow the Allies' advance from the south. Creating a memory bank for a town that lost its heritage and physical identity is fitting. The place where memory was destroyed has become the universal symbol of memory.

What’s the relationship with the town of Pieve Santo Stefano and the Tuscan surroundings?

NC: The relationship with Pieve Santo Stefano, the tiny town in Tuscany, is a relationship that the Archive had to achieve. It wasn’t easy at the beginning, as, I think, it’s never easy for institutions and projects that have a national or global vision in small places.

Since the beginning, the project had the ambition to collect the memory, the stories, of every Italian, saving the Italian autobiographical heritage. While there were many local archives all around Italy, there weren’t any national ones.

We worked hard to make a connection with Pieve, initially, with the project Pieve ’44, where we interviewed people in Pieve to remember the dramatic moment where Pieve was destroyed almost completely, and we continue doing it year after year during Premio Pieve, trying to involve locals in the Prize.

For instance, in the last few years, we’ve organized the food for the Prize volunteers within the Pieve local businesses with an operation called Food Raising, that ends with a big lunch offered by restaurants and wine shops. Not to be forgotten, also, is the Commissione di lettura, (reading commission) a group of local readers that have been meeting once a week for 30 years, to discuss stories enlisted in the Archive, and make a first choice toward the Prize. It’s defined as a brilliant idea, giving to the common people the power and responsibility to read all the content first.

Finally, the Piccolo Museo del Diario (Little Museum of Diaries), our experiential path through the memory by Interaction Design Studio DotDotDot and one of the most innovative museums in Italy, facilitated the relationship with Pieve people who now perceive the Archive as part of their heritage—they’re proud of it.

We also make an effort to keep the Archive open every weekend to give people the chance to identify with the Archive’s stories and work, with an incredible number of resulting visitors. In the surroundings, the Archive started collaborations with Anghiari, developing a Memory Route across the valley of memory, and Arezzo, the closest big city, or Città di Castello, in the Umbria region. It’s important not to be isolated locally, being a national institution, and being deeply-rooted in our territory.

What impact does Archive and the Museum of Memory have on visitors?

NC: We can say that Piccolo Museo del Diario and the Lenzuolo di Clelia (Clelia bed sheet) are a way to engage with people emotionally and experientially: the visitors are very involved emotionally and they spend a long time inside the Museum, even though it’s small, as the word says.

The engagement is guaranteed: everybody finds a story there that somehow speaks to them. The interactive attractions that contain the digital memory develop a quick and deep relationship with the audience, and the story of Vincenzo Rabito, which spans the whole 20th century told by a brilliant, narrative case study, is surprising and, again, very engaging. Clelia’s masterpiece speaks to everybody’s heart, and completes the experience pathway in the Little Museum of Diaries.

Archive founder Saverio Tutino. Photo: Luigi Burroni

How can people get involved in the Archive and become part of the memory community?

LV: There are many ways to be involved and support the work of the Archive. The first is to spread the word, share the content, let people know about this institution and keep the buzz about us alive. The more well-known the Archive is, the bigger its community gets, and certainly it will be easier to reach potential donors.

Then, one can apply to volunteer. Much can be done, even away from the Valtiberina, in Tuscany. Some volunteers transcribe diaries, others do the translations, some help us organize events around the world. We have to admit, nonetheless, that the best way to feel part of the Archive is by coming to Pieve Santo Stefano—by choosing to stop in this small town while travelling in Italy. The experience one can have here, surrounded by the stories of the people who left in this very place a track of their existence, is really touching and truly unforgettable. Whoever has passed by Pieve has hereafter become the best ambassador of the cause of memory.

##